Carolina Snowball

For around 13 years, an albino female bottlenose dolphin lived in the water of Beaufort County, SC. She was a local celebrity and became to be known as Snowball. It was this celebrity status that would lead to her unfortunate fate.

Captured: August 4, 1962

For around 13 years, an albino female bottlenose dolphin lived in the water of Beaufort County, SC. She was a local celebrity and became to be known as Snowball. It was this celebrity status that would lead to her unfortunate fate.

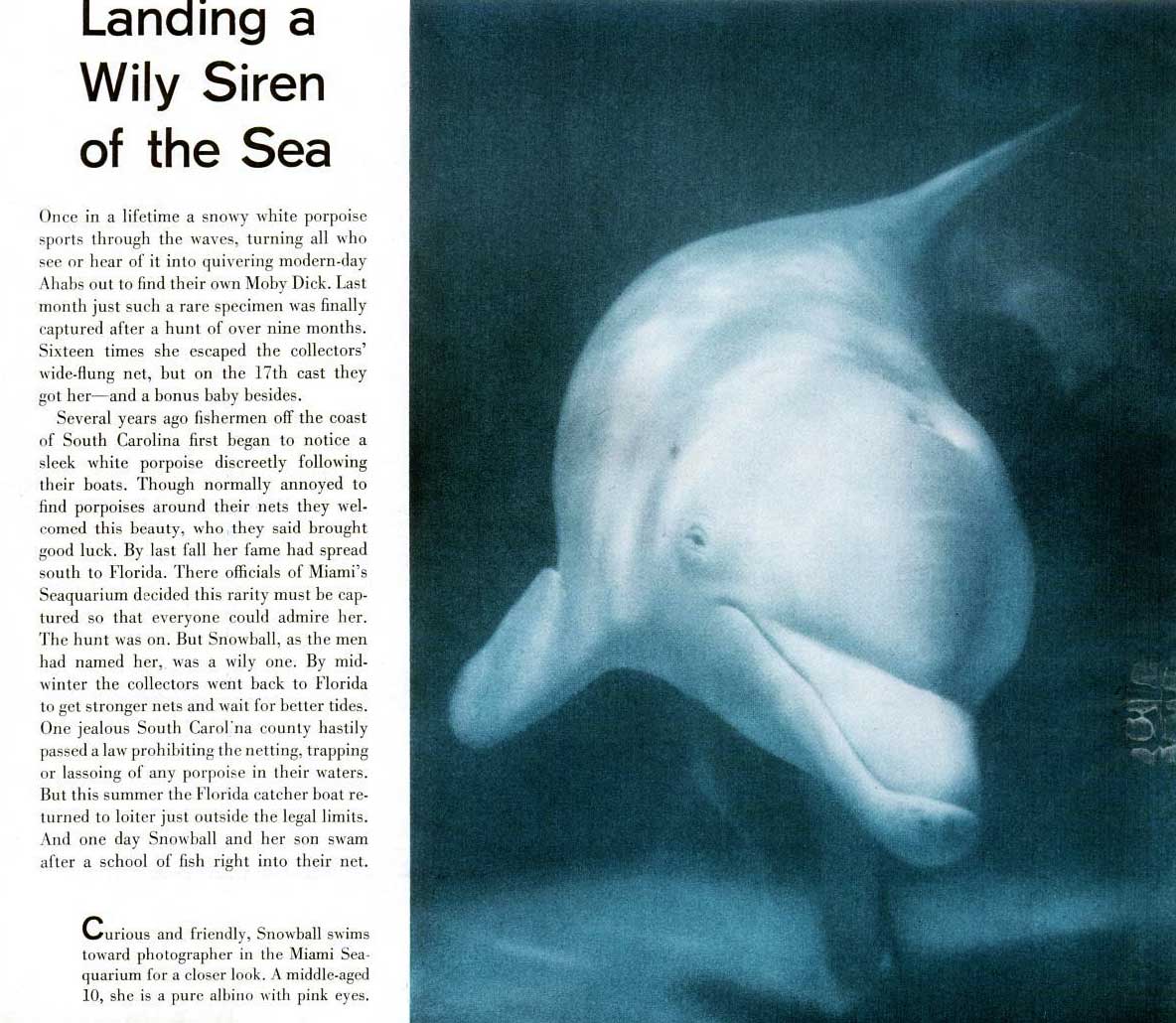

LIFE Magazine noted that Carolina Snowball escaped the nets 16 times. But on the 17th cast, she was finally captured in St. Helena Sound in Colleton County, SC, and brought to the Miami Seaquarium, where she suffered from sunburn and squinted in the hot Miami sun.

Citizens and leaders of Beaufort County were so outraged that they passed a law protecting dolphins in Beaufort County in 1962. This law led to a statewide dolphin protection law, the first in the United States. In 1972, the National Marine Mammal Protection Act was passed to protect dolphins, whales, and manatees.

Three years later, Carolina Snowball developed an infection at the base of her tail. One day she began swimming erratically and, to the horror of tourists watching, she veered into the tank’s window. She died on May 4, 1965. The necropsy showed that she lived with all sorts of problems. She had a stomach tumour as large as a tennis ball, cirrhosis of the liver, emphysema, cysts embedded in several organs, and muscles full of parasites.

Her son was captured alongside her and named Sonny Boy in honour of Captain Sonny Gay, the South Carolina fisherman who first told Captain Gray about Snowball. Captain Bill Gray became the Director of Collections at the Miami Seaquarium, where he worked and authored several books until his death in the early 1980s.

Sonny Boy lived 11 years at the Seaquarium until he died in 1973.

There have been several books about her, and a movie called ‘The Prince of Tides’ includes her story; in this fictional tale, local children freed Snowball and brought her home, and an episode of the TV Series ‘Flipper’ was based loosely on Carolina Snowball and includes actual footage of her capture.

The Miami Seaquarium made a fibreglass replica of her, and for a while, they had a display commemorating Snowball’s life before she was resigned to a storage shed.

Decades later, Kevin Vanacore, fascinated with Snowball from childhood, rescued it and had it professionally rebuilt.

Vanacore tracked down a former curator of the Seaquarium to find out about it being in storage. He even uncovered a story that the model ended up in Biscayne Bay during Hurricane Andrew. Someone returned it to Seaquarium management, which returned it to the forgotten exhibit pile behind some buildings there.

”I even offered to give them a replacement, and it still was difficult to get anyone to work with me. They had the most historical marine mammal that ever lived, and they treated it like a forgotten photo.

Kevin Vanacore

Captain Bill Gray, tells the story of the capture of the white dolphin in his book ‘Friendly Porpoises’.

A couple years after the Miami Seaquarium had opened in 1955...

A couple years after the Miami Seaquarium had opened in 1955 and developed the world’s foremost performing dolphin attraction, a young man came in to see me. “Would you be interested in a white dolphin?” he asked. After looking him over critically and deciding he might know what he was talking about, I said, “Yes, have you got one?” “No,” said he, “but I know where there is one.”

I thought it quite possible because I had actually seen one several years before that was pure white from its dorsal fin back to its tail. This was one of a large herd of normal dark grey-colored Tursiops truncati cruising off shore in the clear blue waters on the northeast side of the Bahamas. That was before dolphins came into vogue as leading attractions in aquariums. However, I have thought many times since of what a wonderful specimen it would be to exhibit. Anyway, I never saw it or any like it since.

Now this man insisted that he knew where there was a dolphin as “white as snow.” My blood tingled a little as I questioned him and decided he was telling the truth. He told me that his family operated a fleet of shrimp trawlers near Beaufort, South Carolina, and it was not unusual for this white dolphin, along with others, to come in by the shrimp boats tied up at the dock where they sorted the catch and threw the unwanted fish overboard. Here the dolphins got a free and easy meal and were often only a few feet from the boats. They were never molested and so had become quite tame. This all sounded very plausible, but since the Seaquarium is some five hundred miles away from Beaufort, it seemed too far to go on a wild-goose chase. I agreed that if he would have someone take a photo of the dolphin and send it to me I would bring our boats, crew, and dolphin nets and try to capture it. Also, if successful, we would pay him well for it. This all seemed to his satisfaction. He would write me and send the photo as soon as he returned home. After weeks turned into months with no response to my follow-up letter, I gave up home and eventually forgot about it.

About four years later, in 1961, my top assistant, Captain Emil Hanson, took a vacation trip...

About four years later, in 1961, my top assistant, Captain Emil Hanson, took a vacation trip along the eastern seaboard. We had obtained a new large-specimen collecting boat and were about to install some modern trawling machinery. Therefore, Emil, stopped at this important shrimp fisheries center near Frogmore, South Carolina, to gather information on the most practical shrimp-trawling gear. During his inspection of the various boats, he met a captain who mentioned the fact there was a white dolphin frequently seen in these local waters. Emil was much interested so Captain Sonny Gay then invited Emil to go out the next day and see for himself.

“There is no question,” said Emil, “it is very definitely white.” They saw it many times during the day. Captain Sonny told Emil that he had stopped in at the Miami Seaquarium three or four years previous and talked to a Captain Gray who was quite interested in securing it. However, he explained that, after talking to me, he noted the animal had changed its habit of coming up in the creek to the docks and stayed mostly out in the deep open sound. For this reason he had given up the idea of capturing it. This explained why I had heard no more from him.

Emil was thrilled and immediately began to consider how it could be captured. He spent a couple days more studying the situation and gathering all pertinent information as to the kind of gear and equipment that would be necessary if we decided to go after it. When Emil returned home we discussed the possibility of capturing this creature. Now, catching dolphins in Florida waters was no problem for us. We also had nets and gear suitable for our south Florida waters. However, it was not at all practical for dolphin catching in St. Helena Sound. Needless to say we decided to try it. Nothing could be more exciting and gratifying than to catch a real white dolphin.

After considerable preparations for this venture...

After considerable preparations for this venture, in November, 1961, we cleared out the inlet at Miami and headed north. High winds and rough sea made it desirable to use the Inland Waterway after the first day out. We made the five-hundred-mile run in a week’s time and arrived, filled with anticipation, in St. Helena Sound on a quiet and beautiful day. The object of our mission was sighted well out in the sound and we followed her about all afternoon. Once she ventured into water shallow enough to warrant trying our net, but we did not do so because we were expecting a motion-picture camera crew to arrive by car the next day to film the entire operation and capture. After feasting our eyes on this beautiful white creature for hours, we headed in to the shrimp dock at Village Creek to await the arrival of our photographers.

The next day we cruised out into the sound with six pairs of eyes scanning the waters in search of Snowball and we located her about noon. Our excited photographers fell all over themselves in their efforts to snap photos. The water was smooth and we had no trouble following this gleaming mammal and they snapped some close-ups. We had seen a lot of Snowball by now and from observation had discovered she was a female. Our conclusion was based on the fact that there was a half-grown baby close to her side each time she rose for air. This proved to be more exciting as we hoped to capture both her and her off-spring. What a fabulous exhibit that would be if we could deliver them to the Seaquarium together!

During the next two weeks we were out at first daylight searching for Snowball, and if we found her, followed patiently, hoping she might stray into an area where we would have a chance of capture by running out net around her. We tried to establish the pattern of her cruising habits, but there were none. She would sometimes separate from the herd, and with her baby take off for a mile or two and then change direction completely.

St. Helena Sound is comprised of some one hundred square miles of water which is fed by dozens of large rivers, and she did not restrict herself to any particular areas. We located her sometimes many miles up in one of the inland tributaries, other times well out at the edge of the ocean. We even searched six days without finding her at all. During the two weeks we had made five attempts to get our net around her. The best chance we had seemed like a sure thing. She, with her baby and half dozen other grey dolphins, had pursued a school of fish over a shallow sandbar where the water was only twelve feet deep. We jockeyed into position to make the “strike,” and the out-board motorboat carrying the end of the net failed to start at the right time. The success of this part of the operation is based on precision timing, so we missed our chance. By the time we were organized to try again, our quarry had vanished. A few days later she and her pack of half-dozen were found in a suitable location at slack tide where there was only ten feet of water.

This time all went as planned and we closed the quarter-mile net and had Snowball...

This time all went as planned and we closed the quarter-mile net and had Snowball, baby, and five large, grey dolphins in the circle. As we pulled the net in, they discovered they were trapped and herded close together in the middle of the circle. We were desperately closing in the net from two net-boats, feeling that luck was with us at last. One of the men helping in my boat even asked what tank I would put her in at the Seaquarium. As the net was gradually being closed the whole lot went into a panic and charged head on into the webbing. Only fifty feet from me, Emil with two other crew members was in the other boat hauling in the net. Two very large bulls struck only six feet from my hands near the cork line on which I was pulling. They escaped and Snowball went through also. This time I was close enough to notice her pink eyes, but that was small consolation. After an hour or more of back-breaking hauling we got our net back on board. We had three ordinary dolphins in the net which we released. One may have been the baby.

After a few more discouraging attempts, we were convinced our only hope of capturing Snowball was to return home and build a special net, designed for these waters. After twenty-two days on the first hunt we tied up our boat and returned to Miami by auto. We immediately ordered the webbing, ropes, corks, and leads we required. However, this being the week before the Christmas season, our material was misplaced on a moor truck line between Baltimore and Miami, resulting in a two-week delay. After building the net, which took eight days, we loaded it on our large truck and returned to our boat and equipment at Village Creek. By this time the shrimping season was drawing to a close and the winter weather had set in. We were not too discouraged by this, however. We donned winter clothing and with our new net on board started out.

We found the change of weather hampered our chances considerably.

We found the change of weather hampered our chances considerably. The high winds, not experienced during our former efforts, kept the sound whipped into a mass of white caps. This made it very difficult to find the white dolphin even if she were close by. The shrimp trawlers were laid up so we could not depend on finding the dolphins following them for their free food as usual. The water temperature dropped below fifty degrees which caused most of the shrimp and fish to leave the sound. Nevertheless, we found Snowball several times but not in a position to make a set. She usually gave us the slip after we had followed in her wake for only a few minutes. Her dark baby was still with her. It appeared to be about a year old.

Our dogged persistence did not help much as general conditions became worse. We were forced to admit defeat. After talking with the local shrimp fishermen and taking their advice we made plans to return to Miami and to return the following June or July. At this time the weather conditions would be more suitable and the shrimp and fish would be back in the sound. We headed towards home on a six-day run with the only thing in our live-well being three sturgeon for our exhibit.

We had found the fishermen of Village Creek helpful and friendly during both our sea-hunts, but we had not courted any publicity on the venture since the only sure thing about the capture was that it was not a sure thing, and we didn’t want pictures of empty nets to be the result of our chase. But we had obtained a legal permit to collect fish and dolphins in South Carolina waters, and it became generally known by word of mouth that we were hunting for a white dolphin in St. Helena Sound.

We were therefore dismayed when we learned in April 1962 that a local law had been passed by the South Carolina legislature to make it illegal to capture dolphins in the waters of Beaufort County. This was a shock to us, but most of the local residents around St. Helena Sound were as much surprised to learn that they had a white dolphin living nearby as they were to learn of the law. South Carolina papers editorialized that the law was a great thing, and even proclaimed that the white dolphin was a great tourist attraction for the area.

This seemed perfectly ridiculous...

This seemed perfectly ridiculous since I had cruised at one time five days from day light to dark around St. Helena Sound and its tributaries without spying her once. This beautiful white creature is known to have been in that area for the past ten to fifteen years, but I doubt if four-score tourists had ever seen her. In fact, vey few besides the local fishermen had ever laid eyes on her. That is not what we consider to be a “tourist attraction” in Florida. The General Assembly had enacted “An act making it unlawful to net, trap, harpoon, lasso or molest genus Delphinus or genus Tursiops in the waters of Beaufort County.” The white dolphin is genus Tursiops truncatus. Penalty for violating the law is a fine of not more than $100 or imprisonment for not more than thirty days.

The episode of the law-passing reminded me of an experience I had some years ago at West End, Grand Bahamas. There was a twelve timber, thirty-feet long, which had washed ashore during a hurricane some years before. It was well up on shore on the water side of the Kings Highway. We were in need of it to use in building temporary holding pen for live aquarium fishes. So, I sought out a local who lived nearby and asked him who it belonged to. He thought awhile and said, “I don’t expect it belongs to anybody until some one wants it, then everybody on the Island will claim it.

Emil and Burton Clark, general manager of the Seaquarium...

Emil and Burton Clark, general manager of the Seaquarium, and I discussed the legal situation. We had a legal permit to collect fishes and marine creatures in Carolina waters, which would allow us legally to net the dolphin in the waters of any county except the restricted county. We had followed the white dolphin for days on end in two other counties, so we agreed we should go back and try again in hope of finding her at the right time and tide outside the restricted area.

We felt the time was right in July so we left the Seaquarium and after a five hundred-mile run arrived in St. Helena Sound the night of June 19th. Next day we took up our usual patrol but did not see Snowball. Late next day we found her following the trawlers with a large pod. But she was in the restricted territory, and though we followed until dark she did not leave the area. We were used to this by now so were not dismayed. Over this area of several hundred square miles of water, whether in or out of the prohibited county line there were but few places where we could attempt to put our net around her. Hazards were very deep water, strong currents, snags, too many other dolphins with her. Most important element of all was the fact that if we circled out net around her while she was with a large pod there would be a chance of drowning some of them before we could set them free. Snowball might be one of them.

Reference

Life, Sept. 21, 1962: The Improbable Hunt for the White Porpoise

AP, Sept. 1962: Rare albino dolphin poses problems for Seaquarium