Capture

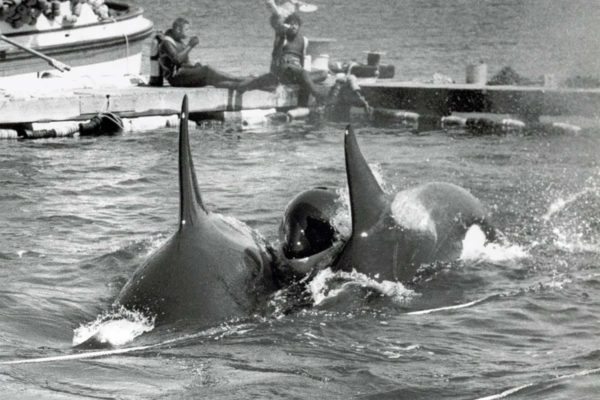

August 8, 1970, Whidbey Island’s Penn Cove orca capture. Led by Don Goldsberry and Ted Griffin of Namu Inc., this event resulted in the deaths of five whales, plus the removal of seven calves from the Southern Resident Orca L Pod. Among the calves captured was the female orca, “Lolita”, still held at Miami Seaquarium.

The Southern Resident orcas of Puget Sound were herded into Penn Cove on Whidbey Island by explosives, spotter planes and speedboats. Divers in wetsuits used ropes, lassos, nets, and nooses to separate the young.

Adult orcas would not leave; piercing, screaming vocalizations were heard incessantly, both above and below water. When they had finished lifting the last captured orca from the water, the family quietly turned toward open water and left the cove. Their cries still haunt the memories of locals and even those who participated in the capture.

Many witnessed the 1970 event. “Traffic was stopped on Highway 20. People lined the bluffs and watched. The whales were vocalizing so loud, it was heard for miles. That happened in 1970, and they did it again in 1971.” said Howard Garrett of Orca Network.

“I remember I stopped over there right close to them with my children who were very small at the time, and they kept saying: ‘Why are they crying? They’re crying.'” said witness Lyla Snover.

Five whales, including four baby whales, drowned.

A twenty-foot female became entangled in the nets and drowned after a desperate attempt to reach her calf. Her drowning was reported in the Whidbey News-Times, the Seattle Times, and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer soon after, fueling the fury of animal-rights activists.

It would turn into a two-week-long ordeal.

John Crowe, an 18-year-old diver hired by Griffin and Goldsberry, later admitted that he and two other men cut the three dead calves open, “fill them with rocks, put anchors on their tail, and sink them.” For months, the deaths went unknown then their bodies started washing ashore. At least one was still attached to a 75-pound anchor.

Six years later, this discovery played a significant role in a court decision that banned SeaWorld from ever capturing another orca in Washington State.

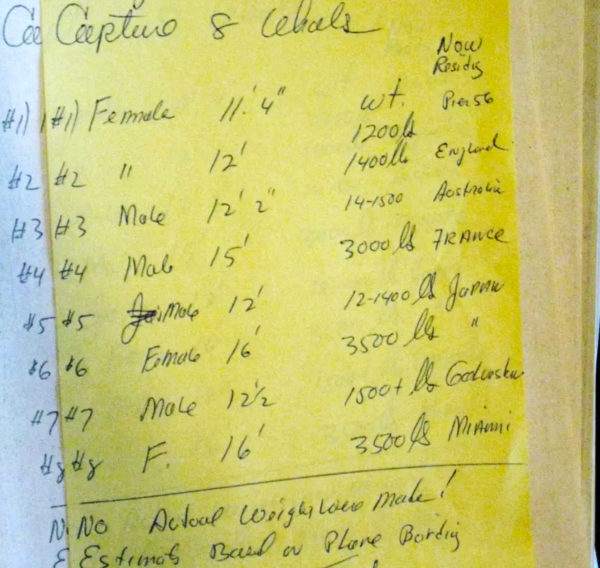

A flatbed truck transported the newly captured orcas to the Seattle Marine Aquarium. Calls were made to aquariums worldwide announcing that orcas were for sale. All sold to marine parks for a reported $20,000 each, bound for the USA, France, England, Germany, Australia, and Japan.

Seven orcas were taken into captivity.

- Winston – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Windsor Safari Park, England > SeaWorld San Diego, California. Death – April 28th, 1986

- Tokitae (Lolita) – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Miami Seaquarium

- Ramu IV – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Unnamed facility, San Francisco > Marineland Australia, Queensland. Death – August 12th, 1971

- Jumbo – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Kamogawa Sea World, Japan. Death – July 1974

- Lil’ Nooka – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Sea-Arama Marineworld, Texas. Death – March 18th, 1971

- Chappy – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Kamogawa Sea World, Japan. Death – April 1974

- Clovis – Penn Cove > Seattle Marine Aquarium > Marineland Antibes, France. Death – February 1973

Dr Jesse White, the veterinarian for the Miami Seaquarium, came to Washington to select one. He admired a particular little female and soon chose her. Dr White had visited a curio shop in Seattle and saw the name Tokitae on a carving, a name he bestowed on the little whale who seemed “so courageous, and yet so gentle.”

On September 24th, 1970, Tokitae arrived at the Seaquarium. A former Seaquarium employee, Pat Sykes, remembered her early days at the aquarium. She said, “The skin on her back cracked and bled from the sun and wind exposure. She wouldn’t eat the diet of frozen herring. At night, she cried.”

She joined another Southern Resident Orca named Hugo, captured at about 4-6 years of age, in February 1968 in Vaughn Bay, nr. Puget Sound, Washington. Their tanks were several hundred feet apart, and they would call out to one another, so trainers decided they would be compatible and put them together in a small circular tank called, The Whale Bowl.

Hugo banged his head against the walls of his tank on many occasions, once slicing the tip of his rostrum off when he broke the thick glass of the viewing window. Veterinarian Jesse White sewed his severed rostrum back on. In March 1980, he rammed the wall of the tank and died. The official report said he died of a brain aneurysm. Hugo had spent 12 years in captivity at the Seaquarium; his body was allegedly unceremoniously disposed of in the Miami Dade landfill.

”The pool where Lolita has spent most of her life — where she watched Hugo die — is 80 feet long by 35 feet wide, with a depth of 20 feet. Lolita herself is 22 feet long. In the wild, orcas dive to depths of several hundred feet.

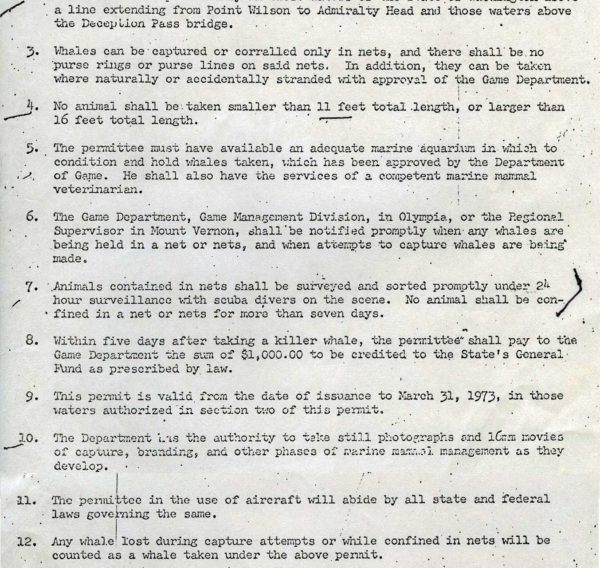

In 1971, following public outcry, the state of Washington set limits and charged permit fees of $1,000 per orca in an attempt to regulate the captures.

By 1972, Griffin, his life, marriage and finances in ruins, had quit the whale-catching business, selling it to Goldsberry, who then resold the company to SeaWorld. Griffin informally changed his name and moved to Eastern Washington, where he sought obscurity, working as a day labourer for as little as $2 an hour.

The federal government enacted the Marine Mammal Protection Act, ending whale captures in the U.S. NOAA granted SeaWorld an economic hardship exemption allowing them to continue capturing.

By 1976 some 270 orcas were captured — many multiple times — in the Salish Sea. At least 12 orcas died during capture, and more than 50, mostly critically endangered southern residents, were kept for captive display. Captures in the Pacific Northwest ended after the notorious Budd Inlet orca capture.

Ralph Munro, an assistant to Washington State Governor Dan Evans, was sailing in Puget Sound and reported that the SeaWorld capturers were using aircraft and explosives to herd and net the orcas, a clear violation of the terms of their collection permit.

Munro reached out to the press, and by the next day, the hunt was front-page news around the region. In a news conference, Washington State Governor Dan Evans announced his opposition to the hunt, and within hours the state obtained a federal restraining order prohibiting SeaWorld from moving the orcas, which were by then circling in nets surrounded by more than 100 opponents in kayaks, canoes and on the beach.

SeaWorld went to work to quash the injunction. Legal wrangling with the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and back landed the controversy in federal court in Seattle, where demonstrators lined up on the courthouse steps and down the street to demand a stop to the hunts; and ordered to relinquish their permit-granted right to collect orcas off Washington. The orca hunt in Budd Inlet was the last in America.

Chastity (now Chaz) Bono, the two-year-old child of pop duo Sonny and Cher, feeding the captive killer whale, Lolita, at the Seaquarium in Miami, Florida, in 1973. Avalon /Getty Images

A few years ago, Ted Griffin visited Tokitae and stated he had no regrets and his motives were never understood.

“I wanted people to see the whale the way I see the whale they are shooting at seals, anything that pops up in the water. I am saying, ‘What are you doing? There is something behind that.'”

“Because I want to humanize that person in the sea. Up until this time, it is just a beast; it is nothing. I see it as saving the whale from all this mischief, all these bad thoughts. How can I get the public to understand that this is not what they think it is?”

“I had no idea at the time that would start a thought pattern that would bring my career to an end.”

Wild orcas swim hundreds of miles, diving as deep as 500 feet; alone in her tank, Tokitae circles 35 feet and can only dive as deep as 20 feet in a small area in the centre of the tank. At least 40 other captives from her extended family died by 1987, yet she remains, day after day, in a crumbling tank she can barely turn around in. Her perseverance is a mystery; she continues to show the world her courage and gentle spirit.